Birth rates are falling globally. In fact, the fertility rate in the U.S. hit a record low of 1.64 expected births per a woman’s lifetime in 2020.

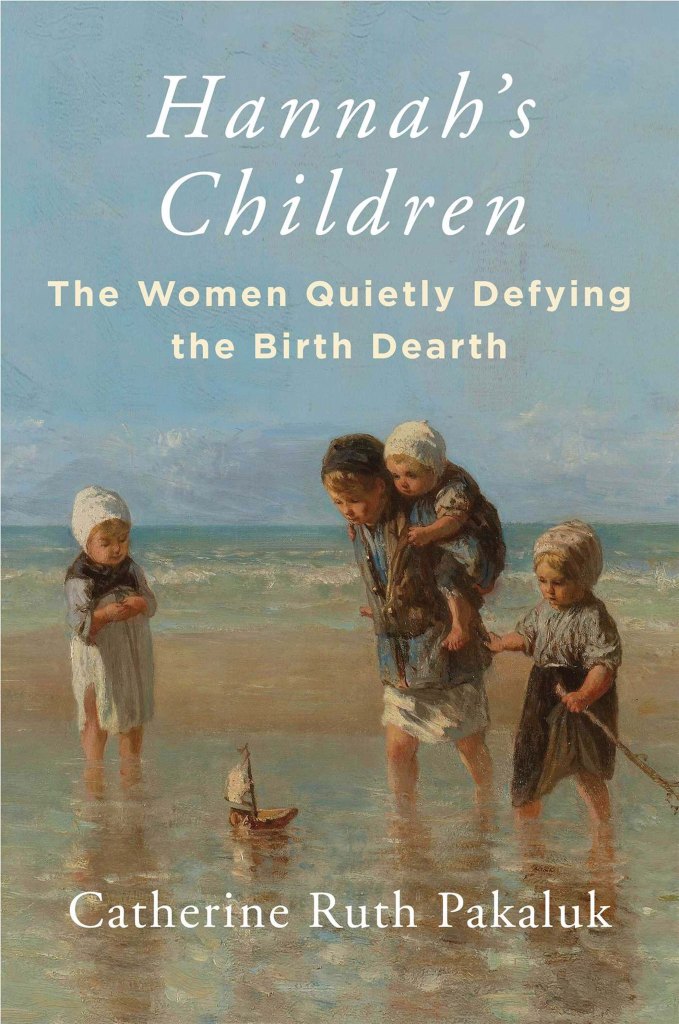

At the same time, about 5 percent of women in the nation currently have five or more children on purpose. Catherine Pakaluk, Ph.D ’10, a Catholic University economist and mother of eight (and stepmother of six), wanted to find out why, both academically and personally. Her new book, “Hannah’s Children: The Women Quietly Defying the Birth Dearth,” offers an intimate view into the lives of families around the country who have decided to pursue large families.

Pakaluk spoke with the Gazette about what she learned. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What drew you to this topic, and why do you think it’s an important one to talk about in the current moment?

As an economist I’ve been interested in questions related to population growth as it relates to labor market and human development for a long time. But in the last 10 years, especially since the Great Recession, it’s become increasingly a puzzle: Why have birth rates been declining so rapidly and why aren’t they responding to some of the [policy] things that we would assume they would respond to? I thought this was really interesting.

I’m also interested in women’s choices and labor market choices. I was noticing that around the world, countries are about to get kind of bossy about women having children. They’re applying bigger and bigger incentives to try to get people to have kids. It’s becoming a mounting policy concern, with nations wanting people to have kids. That always sounded a little alarming to me, so I wanted to see what we could learn. Falling birth rates represent one of the main concerns for the contemporary political economy, mainly because the social welfare programs [like Social Security] are creaking and straining under these decreasing birth rates.

In your book, you talk to women who are defying the birth rates by having five or more children. You found that they faced misperceptions by those around them about why they had so many children. What were they?

The main misperception would be that the kind of women who decide to have a lot of children — whether they have careers or not — must be part of religious cults or are people who lack full human agency. That’s concerning that the assumption is that other people are making decisions for these women, be it their religious leaders or husbands. That’s not the case.

The other main misperception that I heard commonly is that women who have a lot of children probably reject modern forms of birth control, either because they don’t know how to access it or don’t believe in it. I knew that wasn’t true in my life, but I thought it was worth exploring.

Nobody I talked to said that not using birth control was the reason for their family size. Some women did prefer to use fertility awareness methods for spacing their children, but I found that whether they did or didn’t use birth control they truly and intentionally chose to have their children.

Did you find any connection between religion and family size?

What I found (and this will sound very economist-y of me) is that the choice process followed a cost-benefit, rational choice model. In that framework, when people make a decision they weigh the expected joys or benefits with the expected costs.

In the case of women making purposeful decisions to have large families, they definitely described the costs in their choice. What I heard was an acute description of the costs, which didn’t seem to be expense-driven, but were more about waking up every two hours for a long time, the effects on their bodies, the trade-offs made in regard to their personal identities.

But when it comes to faith and religion, what I heard was a uniting around the idea that children are a great blessing. That provided a huge benefit to the women in my study that outweighed the significant personal costs. Faith played a role of tipping the scales toward having more children.

I will say, I didn’t talk to people who had smaller family sizes. That wasn’t the purpose of this project. But this group was a group of people who really felt that they began their families intentionally, experienced great joy, felt the blessings were tangible in their lives, so they decided to keep going.

Studies have shown many women want more children than they eventually have — you call this the fertility gap. What’s causing this?

If I could easily answer what’s causing the gap, I’d probably be a candidate for the next Nobel Prize. But in all seriousness, I think of recent Nobel laureate Claudia Goldin’s work, which helps us see what’s going on. I would point back to her work on the “Power of the Pill” and what the pill does in shaping the lives of American women. It opens the choice set, right? And, of course, I think her more recent work on women’s labor is so insightful and helps us see that when you change the choice set for people, who are rational agents making decisions, you create a new comparison class for the goods that you can choose.

What hormonal contraception did in the 20th century is it provided women with more choices. If you wanted to pursue a career, you didn’t have to give up marriage. In the past, if you wanted to go to college or have a profession, you had to give up marriage and partnership. What ends up happening when you broaden the choice set is that a lot of people want both. And so they end up choosing a little bit less of each. So if, objectively speaking, you might have chosen three kids, you might be okay with the trade-off of fewer children to also have a profession.

What we’re seeing is the outcome of a constrained optimization. People are choosing the bundle career and family, and in this constrained world there’s only so much time. One of the women in my study said, “Look, there’s some things that are best done young.” She says, of her medical training, “I would never want to go through that later in life.” But it’s also the easiest time to build the family size that you might want to have. So you have these two things that are in tension. I don’t think that’s an enormous mystery.

Most of the families that you talk to in the book describe themselves as happy and healthy. Did you speak to any who are struggling — economically, emotionally, physically — with dealing with a larger family?

My sample is not representative, and people volunteered to talk to me. So I’m sure, in that sense, there’s a bit of a bias in favor of people who are pretty happy with how things were going. But within that sample, I intentionally looked for families who are at all ends of the wealth distribution. I talked to families who were either on food stamps or eligible for food stamps or other forms of income supplements.

I also spoke to people who were going through postpartum depression, women who were struggling to manage ongoing mental illness, depression, or anxiety. But I would say that everybody that I talked to, mostly due to the study design, felt that whatever troubles they experienced were worth it. I certainly don’t believe having a large family is any guarantee that everything will work out well. However, the purpose of the book was to examine motive: What could lead people to have more children than normal?

The women you spoke to were fully on board with their decisions to devote so much of their lives to their families, even while acknowledging that it took incredible sacrifice. Is there anything policymakers can glean from their experiences that can help make things better for parents and families overall?

I don’t think women have children thoughtlessly. I think a lot of blood, sweat, and tears goes into the decision. And I would say that the same thing must be true for people who choose not to have children.

The sometimes flippant nature of political discourse on women’s family and fertility decisions doesn’t take the issue as seriously as it should. The idea that we could influence a couple with $1,000 more of a tax break or a baby bonus is almost offensive. Or even to say you can influence people with a lot of money, like $200,000 to $400,000 per baby, that it would move the needle. I think this is a really sacred and private decision.

So if we know that, what could make things easier? One thing that came out of this work was the story of faith, but I think that story has just as much to do with community and social support. Where can we put our dollars (in a fiscally responsible way) that helps people in this way?

What I took away from my study was that whatever we can do from a policy perspective to protect and enlarge spaces — religious or not — for people to grow and develop, those are the kinds of things people should think about.

I also think about role modeling. Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman’s book “What Are Children For? On Ambivalence and Choice” is so interesting. They look at these deep-seated fears that people have about making the choice to have children. But if you can see others who have gotten over the hurdles, you might be more open to it. I think policymakers could think harder about how we treat faith institutions and think about them as a favored means to provide support to families.

What do you hope readers take away from the experiences of the women in your book?

I wanted to leave people with a message of hope. These are serious topics. But if there’s some people out there defying the odds and not undershooting their own fertility desires, here’s a model of people who are pulling this off.

A lot of times you read the news and see how nobody’s having the families they want to or it’s getting harder and harder. It’s helpful to realize that trends in society are measured in averages. But in fact, many people live lives that are very different from the average.

If we’re interested in building a family, I think there are some concrete lessons from people who have done it. It shows that what’s happening with family size isn’t deterministic. I hope people feel hopeful and optimistic about it, and not like these falling birth rates have to be the whole story of the future.

Source link