Of course he will fire the special prosecutor investigating him if he’s reelected.

In the early 17th century, the English jurist Edward Coke laid out a fundamental principle of any constitutional order: No man can be the judge in his own case. Donald Trump thinks he has found a work-around.

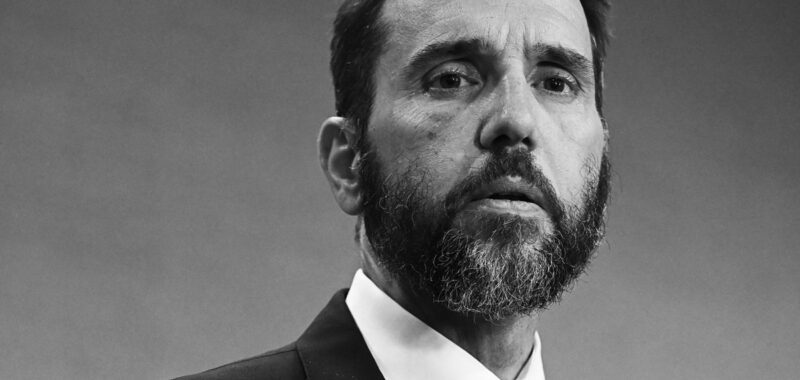

The Republican presidential candidate yesterday confirmed what many observers have long expected: If he is elected president in two weeks, he will fire Jack Smith, the Justice Department special counsel investigating him, right away. No man can be his own judge—but if he can dismiss the prosecutors, he doesn’t need to be.

“So you’re going to have a very tough choice the day after you take the oath of office, or maybe even the day that you take the oath of office,” the conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt, a Trump critic turned toady, asked him. “You’re either going to have to pardon yourself, or you’re going to have to fire Jack Smith. Which one will you do?”

“It’s so easy. I would fire him within two seconds,” Trump said. “He’ll be one of the first things addressed.”

Smith has charged Trump with felonies in two cases: one related to attempts to subvert the 2020 election, and the other related to his hoarding of classified documents at Mar-a-Lago.

Although Trump claims to have many substantive policy goals for his second term, his comments about firing Smith reveal where his true priorities lie. Trump frequently dissembles, but this is a case of him speaking quite plainly about what he will do if he is elected. One major theme of his campaign has been the need to rescue himself from criminal accountability (or, in his view, persecution). Another has been the promise to exact retribution against his adversaries. Sacking Smith would serve both objectives. In another interview yesterday, Trump said that Smith “should be thrown out of the country.”

The scholarly consensus is that Trump has the legal right to fire Smith, and also that such a firing would be a deeply disturbing violation of the traditional semi-independence of the Justice Department. It would also be a scandalous affront to the idea that no citizen, including the president, is above the law. Even if it could be proved that Trump fired Smith with the express purpose of covering up his own crimes, Trump would almost certainly face no immediate repercussions. The Supreme Court this summer ruled that a president has criminal immunity for any official act, and firing Smith would surely qualify.

During the radio interview, Hewitt warned that removing Smith could get Trump impeached. It’s possible. Control of the House is up for grabs in November, and the Democrats might be slight favorites to prevail. But Trump’s first two impeachments made perfectly clear that Senate Republicans, whose votes would be required to convict, have no interest in constraining him. Some of them have already taken the public stance that the prosecutions against Trump are improper—even though no one questions that Trump took classified documents to Mar-a-Lago after he left office, no one has made a coherent defense that he had a right to possess them, and the details of Trump’s election subversion are well known and unchallenged.

These facts will be irrelevant if Trump can simply fire Smith. That’s the power he’s asking voters to grant him.