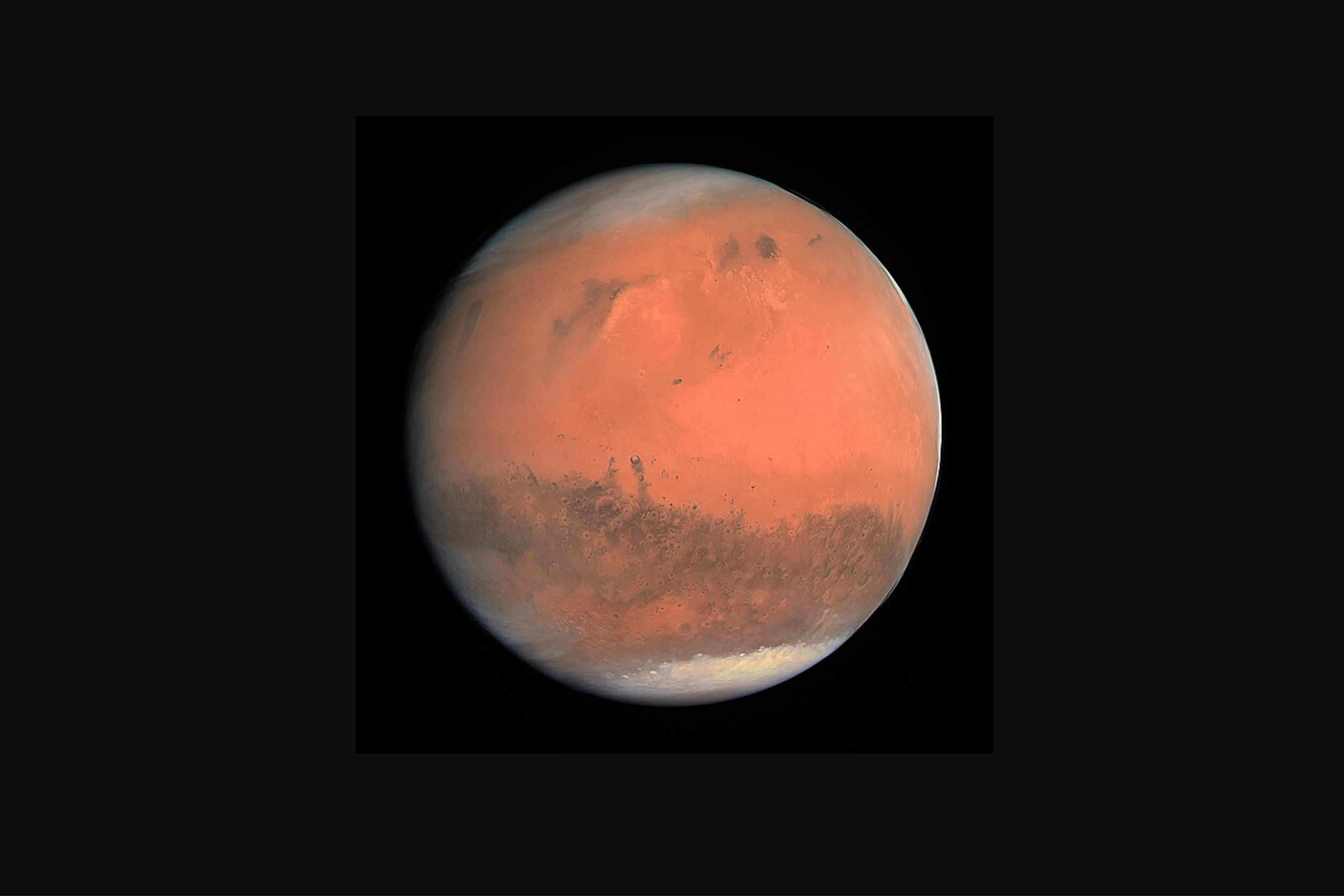

Evidence suggests Mars could very well have been teeming with life billions of years ago. Now cold, dry, and stripped of what was once a potentially protective magnetic field, the Red Planet is a kind of forensic scene for scientists investigating whether Mars was indeed once habitable and, if so, when.

The “when” question in particular has driven researchers in Harvard’s Paleomagnetics Lab in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. A new paper in Nature Communications makes their most compelling case to date that Mars’ life-enabling magnetic field could have survived until about 3.9 billion years ago, compared with previous estimates of 4.1 billion years — so hundreds of millions of years more recently.

The study was led by Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences student Sarah Steele, who has used simulation and computer modeling to estimate the age of the Martian “dynamo,” or global magnetic field produced by convection in the planet’s iron core, like on Earth. Together with senior author Roger Fu, the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Natural Sciences, the team has doubled down on a theory they first argued last year that the Martian dynamo, capable of deflecting harmful cosmic rays, was around longer than prevailing estimates claim.

The researchers simulated the cooling and magnetization of large impact basins on Mars to defend a later dynamo shutdown.

Credit: Sarah Steele

Their thinking evolved from experiments simulating cooling and magnetization cycles of huge craters on the Red Planet’s surface. Known to be only weakly magnetic, these well-studied impact basins have led researchers to assume they formed after the dynamo shut down.

This timeline was hypothesized using basic principles of paleomagnetics, or the study of a planet’s prehistoric magnetic field. Scientists know ferromagnetic minerals in rock align themselves with surrounding magnetic fields when the rock is hot, but these small fields become “locked in” once the rock has cooled. This effectively turns the minerals into fossilized magnetic fields, which can be studied billions of years later.

Looking at basins on Mars with weak magnetic fields, scientists surmised they initially formed amid hot rock during a period in which there were no other strong magnetic fields present — in other words, after the planet’s dynamo had gone away.

But the Harvard team says this early shutdown isn’t necessary to explain those largely de-magnetized craters, according to Steele. Rather, they argue that the craters were formed while the dynamo of Mars was experiencing a polarity reversal — north and south poles switching places — which, through computer simulation, can explain why these large impact basins only have weak magnetic signals today. Magnetic pole flips also happen on Earth every few hundred thousand years.

“We are basically showing that there may not have ever been a good reason to assume Mars’ dynamo shut down early,” Steele said.

Their results build on previous work that first upended existing Martian habitability timelines. They used a famed Martian meteorite, Allan Hills 84001, and a powerful quantum diamond microscope in Fu’s lab, to infer a longer-persisting magnetic field until 3.9 billion years ago by studying different magnetic populations in thin slices of the rock.

Steele says poking holes in a long-held theory is a little nerve-wracking, but that they’ve been “spoiled rotten” by a community of planetary researchers who are open to new interpretations and possibilities.

“We are trying to answer primary, important questions about how everything got to be like it is, even why the entire solar system is the way that it is,” Steele said. “Planetary magnetic fields are our best probe to answer a lot of those questions, and one of the only ways we have to learn about the deep interiors and early histories of planets.”

Source link