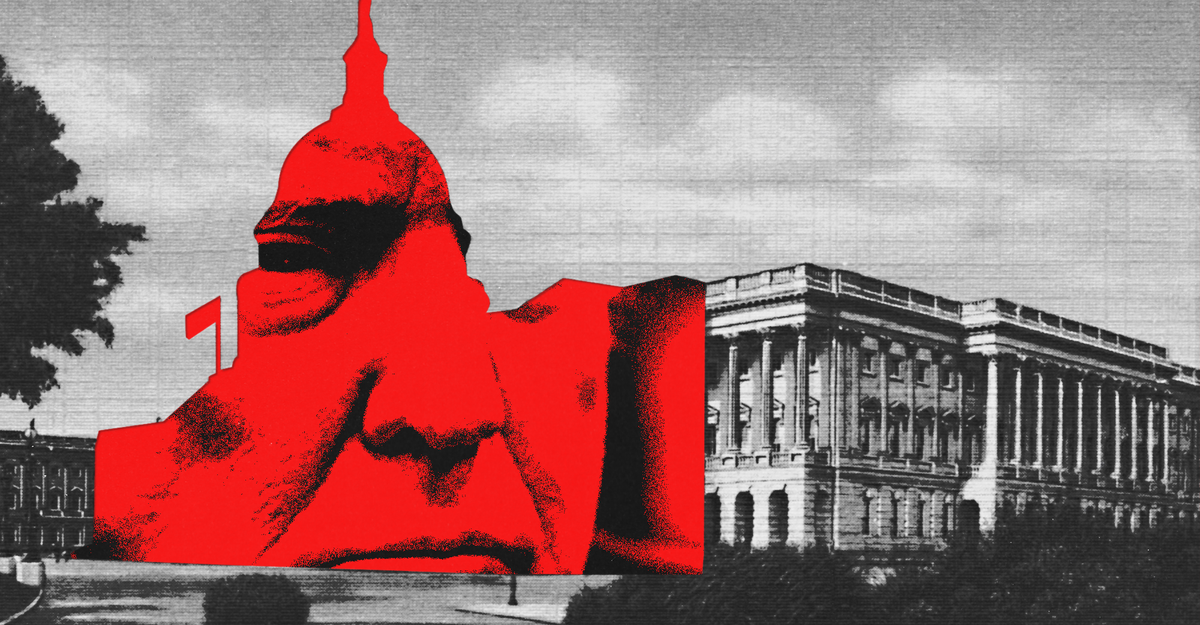

Power-hungry presidents of both parties have been concocting ways to get around Congress for all of American history. But as Donald Trump prepares to take office again, legal experts are worried he could make the legislative branch go away altogether—at least for a while.

Several of Trump’s early Cabinet nominees—including Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and former Representative Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii—have drawn widespread condemnation for their outlandish political views and lack of conventional qualifications. Their critics include some Senate Republicans tasked with voting on their confirmation. Anticipating resistance, Trump has already begun pressuring Senate GOP leaders, who will control the chamber next year, to allow him to install his picks by recess appointment, a method that many presidents have used.

The incoming Senate majority leader, John Thune of South Dakota, has said that “all options are on the table, including recess appointments,” for overcoming Democratic opposition to Trump’s nominees. But Democrats aren’t Trump’s primary concern; they won’t have the votes to stop nominees on their own. What makes Trump’s interest in recess appointments unusual is that he is gearing up to use them in a fight against his own party.

If Senate Republicans block his nominees, Trump could partner with the GOP-controlled House and invoke a never-before-used provision of the Constitution to force Congress to adjourn “until such time as he shall think proper.” The move would surely prompt a legal challenge, which the Supreme Court might have to decide, setting up a confrontation that would reveal how much power both Republican lawmakers and the Court’s conservative majority will allow Trump to seize.

“None of this has ever been tested or determined by the courts,” Matthew Glassman, a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Government Affairs Institute, told me. If Trump tries to adjourn Congress, Glassman said, he would be “pushing the very boundaries of the separation of powers in the United States.” Although Trump has not spoken publicly about using the provision, Ed Whelan, a conservative lawyer well connected in Republican politics, has reported that Trumpworld appears to be seriously contemplating it.

Trump could not wave away Congress on his own. The Constitution says the president can adjourn Congress only “in case of disagreement” between the House and the Senate on when the chambers should recess, and for how long. One of the chambers would first have to pass a resolution to adjourn for at least 10 days. If the other agrees to the measure, Trump gets his recess appointments. But even if one refuses—most likely the Senate, in this case—Trump could essentially play the role of tiebreaker and declare Congress adjourned. In a Fox News interview yesterday, Speaker Mike Johnson would not rule out helping Trump go around the Senate. “There may be a function for that,” he said. “We’ll have to see how it plays out.”

Presidents have used recess appointments to circumvent the Senate-confirmation process throughout U.S. history, either to overcome opposition to their nominees or simply because the Senate moved too slowly to consider them. But no president is believed to have adjourned Congress in order to install his Cabinet before. “We never contemplated it,” Neil Eggleston, who served as White House counsel during President Barack Obama’s second term, told me. Obama frequently used recess appointments until 2014, when the Supreme Court ruled that he had exceeded his authority by making them when Congress had gone out of session only briefly (hence the current 10-day minimum).

Any attempt by Trump to force Congress into a recess would face a few obstacles. First, Johnson would have to secure nearly unanimous support from his members to pass an adjournment resolution, given Democrats’ likely opposition. Depending on the results of several uncalled House races, he might have only a vote or two to spare at the beginning of the next Congress. And although many House Republicans have pledged to unify behind Trump’s agenda, his nominees are widely considered unqualified, to say the least. Gaetz in particular is a uniquely unpopular figure in the conference because of his leading role in deposing Johnson’s predecessor Kevin McCarthy.

If the House doesn’t block Trump, the Supreme Court might. Its 2014 ruling against Obama was unanimous, and three conservative justices who remain on the Court—John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito—signed a concurring opinion, written by Antonin Scalia, saying they would have placed far more restrictions on the president’s power. They wrote that the Founders allowed the president to make recess appointments because the Senate used to meet for only a few months of the year. Now, though, Congress takes much shorter breaks and can return to session at virtually a moment’s notice. “The need it was designed to fill no longer exists,” Scalia, who died in 2016, wrote of the recess-appointment power, “and its only remaining use is the ignoble one of enabling the president to circumvent the Senate’s role in the appointment process.”

The 2014 ruling did not address the Constitution’s provision allowing the president to adjourn Congress, but Paul Rosenzweig, a former senior official in the George W. Bush administration and an occasional Atlantic contributor, told me that the conservatives’ concurrence “is inconsistent with the extreme executive overreach” that Trump might attempt: “As I read them, this machination by Trump would not meet their definition of constitutionality.”

Thanks in part to those legal uncertainties, Trump’s easiest path is simply to secure Senate approval for his nominees, and he may succeed. Republicans will have a 53–47 majority in the Senate, so the president-elect’s picks could lose three GOP votes and still win confirmation with the tiebreaking vote of Vice President–Elect J. D. Vance. But the most controversial nominees, such as Gaetz, Kennedy, Gabbard, and Pete Hegseth (Trump’s choice for defense secretary), could struggle to find 50 Republican votes. And as Thune himself noted in a Fox News interview on Thursday night, Republicans who oppose their confirmation are unlikely to vote for the Senate to adjourn so that Trump can install them anyway.

Thune, who had been elected as leader by his colleagues only one day before that interview, seems fine with helping Trump get around Democrats. Letting Trump defy Thune’s own members and neuter the Senate is a much bigger ask. Then again, if Trump takes his power play to the limit, the new majority leader won’t have a say at all.