My parents are from Cuba and Poland. Growing up, mom and dad hardly ever talked about their pasts before coming to the United States; I only knew how they arrived, and more specifically where: in New York City, where I was born.

Article continues after advertisement

The cultural history of migratory trauma—a cycle of annexations, incorporations, dislocations, assimilations—can often only be processed through its mediation in various forms. Secondhand relations offer what autobiography, history, and the singular first-person novel cannot: an acknowledgment of the friction between memory and documentation, a spotty passed-down account in which there is no whole picture, only pieces—and the desire to reassemble the scraps.

Like many other books by migrant and first-gen authors, my novel VHS explores the ways in which we piece together our memories of home through the stories of others. Superimposing multiple storytellers on the narrative track and avoiding the English language custom of using quotation marks to indicate speech gives permission to readers to consider the slippages between any “original” experience and its perception at present.

The audience serves as a witness and a recorder, shaping the direction of the story being told, empowering more interactive—and inclusive—stories. The books on this list are a testament to the variegated contours of migration; that, like movement itself, the story of migration is not one but multiple: recurrent, coinciding, patchwork, and collective.

As the narrator of VHS admits in the novel’s opening pages: “On the trail of my parents’ exiles, I remain susceptible to detour.”

*

Olga Tokarczuk, Flights (trans. Jennifer Croft)

Winner of the 2018 Man Booker International Prize, Flights is assembled into a hundred and sixteen short pieces with titles like “A Very Long Quarter of an Hour,” “The Achilles Tendon,” “Letters to the Amputated Leg,” and “The Tongue Is the Strongest Muscle.” If Olga Tokarczuk’s polyphonic novel is an itinerary of movement, it’s also a constellation of the body through disparate times and spaces.

As the amorphous narrator admits early on: “Whenever I set off on any sort of journey I fall off the radar. No one knows where I am. At the point I departed from? Or at the point I’m headed to? Can there be an in-between?”

Jennifer Croft’s English translation of Flights celebrates the novel’s explorations of discrepancies and intermediations: between languages, between countries, between generations and genealogies—each susceptible to diffracting lines of flight.

Dubravka Ugrešić, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender (trans. Celia Hawkesworth)

Dubravka Ugrešić’s autobiographical novel, which includes a family recipe for caraway soup, is organized more like a scrapbook, melting the borders between novel and journal, between fiction and autobiography, through a desire to uphold the amateur activity of organizing objects, as if finding a place for such things might also reveal something about the author-narrator’s condition of her own present exile in Berlin.

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender’s prefatory remarks—about a walrus named Roland who died on August 21, 1961; or a week after the Berlin Wall was erected—arrive with instructions for what might otherwise feel like the opening act of a detective fiction: “with time the objects have acquired some subtler, secret connections […] be patient: the connections will establish themselves of their own accord.”

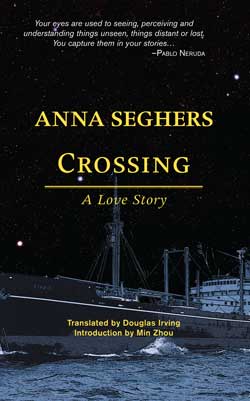

Anna Seghers, Crossing: A Love Story (trans. Douglas Irving)

Many readers might be more familiar with Anna Seghers’s debut novel, Transit, an autofictional account that was adapted for the screen by Christian Petzold in 2018, illuminating the connections and contradictions of migration discourse between the Second World War and today.

Like Transit, which follows the story of a story about a refugee who impersonates a dead writer in an attempt to flee their fascist home, everything told to us on the ship that serves as the setting for Crossing is told to us in secondhand, sometimes even through a more distant frame.

The “I” becomes disintegrated and multiplied, and the narrator, if there is in fact a stable narrator, performs as audience member, without whom the story would not continue. Seghers’s novel after all is called “Crossing,” and one of the novel’s major points is that a story is as rhizomatic as the boat that is carrying its many passengers, speakers and listeners tasked with the role of relaying.

Cristina García, Here in Berlin

The first chapter of Cristina García’s novel in conversations, about a writer—known only as the Visitor—living alone in Berlin, closes with a question that reverses the subject-positions between speaker and listener, between the exiles living in Berlin and the Cuban-American writer who is engaging them in correspondence, to learn something of her own past, the specter of the Soviet Bloc still haunting Latin America.

“Sometimes, Kind Visitor, I long to send letters to the past…but who would write back?” Pages earlier, in the prologue, readers learn that the Visitor, prone to wanderings and a keeper of diaries in her younger years, would not keep a journal in Berlin, nor would she write about herself in the first person: “Rather, she would indulge the luxury of a more distant perspective.”

Through muddling the frames of first and third person, García’s story of the Visitor’s psychic and material dislocation as a Cuban-American becomes the stories of cross-generational exile: the debris of history gathered here in Berlin and glimpsed through a lens that is not just transnational but reciprocal.

Fae Myenne Ng, Bone

Fae Myenne Ng’s debut novel follows Leila, the oldest daughter in a family of three girls in San Francisco’s Chinatown, as she looks back on her life and her family’s history, so much of which has heretofore been guarded in silence. Myenne Ng’s narration experiments with the mediation of the past through distance and memory; each chapter moves further into Leila’s past, so that events that have already been recounted repeat in the present pages later, revealing how we alter our past through a perspective that is always on the move and subject to detour.

Bone moves between worlds and languages; Leila marks the distinctions between using Chinese and English, all the while knowing that her story, in spite of its secrets or maybe because of them, will inevitably be taken up by the community overhearing. “Let them make it up,” Leila remarks, early into her story, which is also an acknowledgment of her own power, and permission, as the novel’s storyteller. “Let them talk.”

Maxine Hong Kingston, The Woman Warrior

Originally subtitled Memoirs of a girlhood among ghosts upon its original publication in 1976, begins with a warning, unless it’s an invitation: “‘You must not tell anyone,’ my mother said, ‘what I am about to tell you.’”

In the harrowing “No Name Woman,” which opens Kingston’s debut book, the narrator’s mother continues to interrupt herself, reminding her daughter not to tell anyone she had an aunt, reminding her that her father does not want to hear her aunt’s name, that her aunt had ever lived, reminding readers, moreover, of the necessity for Kingston to tell this story, and all the others that will follow.

To combat a tradition of generational silences, Kingston requires the fabric of more than her own family’s history but traditional Chinese folklore. The blending of genres is hypnotic; the blur that it produces intentional. As Kingston describes the effects of her mother’s bedtime rituals: “I couldn’t tell where the stories left off and the dreams began, her voice the voice of the heroines in my sleep.”

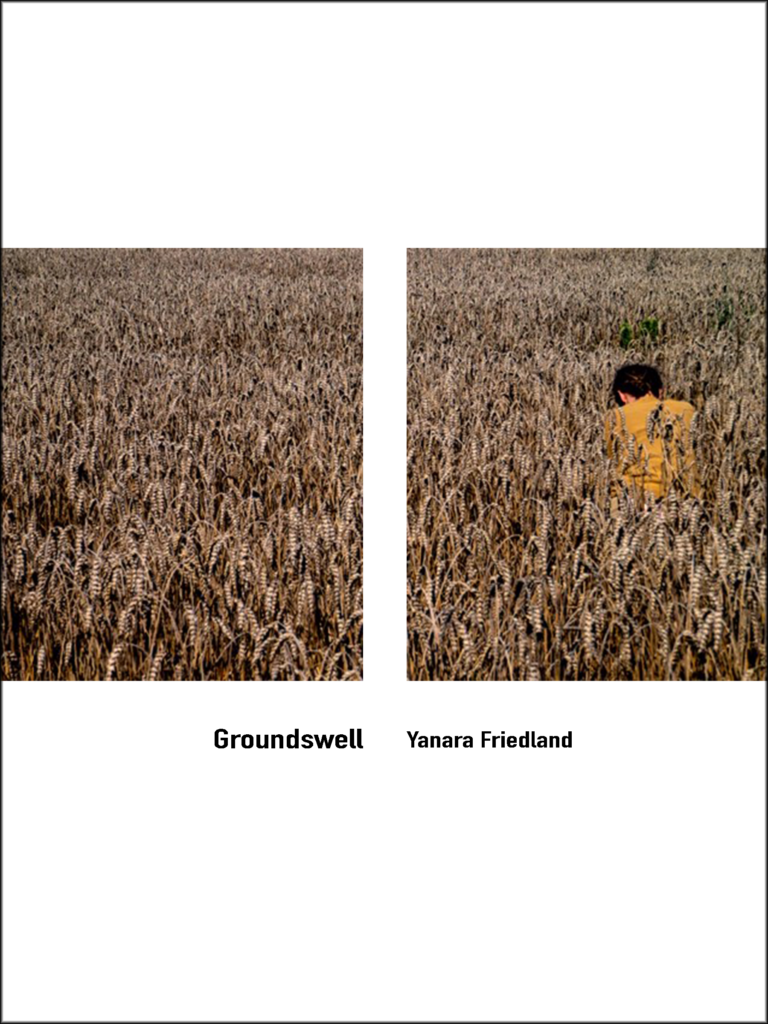

Yanara Friedland, Groundswell

Yanara Friedland’s Groundswell follows the author’s return to Berlin, the city from which, as a child, she’d taken pieces from the wall as she watched it collapse. Pages into her kaleidoscopic memoir in essays, the narrator stumbles upon an archive of German-Polish border stories, located, not surprisingly, underground.

This “Archive of Human Destinies” becomes the engine for Friedland’s excavation of the Cold War, the securitization of so-called homeland that bridges Germany and Poland in the twentieth century with the US, where Friedland now lives, and Mexico in our current moment.

Groundswell’s eclectic arrangement—a constellation of one-word space-times like “River,” “Landflucht,” “Pilgrimage,” “Moonscapes,” “Crossings,” and “Trainstation,” feels inspired by Viktor Shklovsky’s well-known motto in the prologue to his Third Factory (1926), itself a testament to internal exile in newly Bolshevist Russia: “I have no desire to be witty. I have no desire to construct a plot. I am going to write about things and thoughts. To compile quotations.”

Friedland does just that, while intertwining the Arizona desert with the “twin cities” along the banks of the Oder, each of them sites of mutable nationality and the violence of nationalization.

Valeria Luiselli, Lost Children Archive

Lost Children Archive, Valeria Luiselli’s first book written in English, follows a cross-country car trip from New York to Arizona made by a husband and wife (“Ma” and “Pa”) and their two children (“the girl” and “the boy”). As one child observes of his parents’ professions, distinguishing between a “documentarist” and a “documentarian” before revealing a commonality that describes, too, the novel’s structure: “But both of them did basically the same thing: they had to find sounds, record them, store them on tape, and then put them together in a way that told a story.”

So too does Luiselli arrange the text in a way that embeds the narrative’s plot and thematic concerns as elements of form, repurposing sources as a method of composition and a comment on how we construct stories from a wellspring of voices. Each chapter in Lost Children Archive corresponds to the archival boxes riding with the family, hauled in the trunk of the car.

These pieces—reading lists, photographs (taken by Luiselli and attributed to “the boy”), fragmented excerpts of poetry, maps, and other clippings—intermingle with the stories told to the children by their father to pass the time on the long drive as well as the “Elegies for Lost Children” contained within a red book that the mother is constantly reading aloud and recording and which she shares with her son, who ultimately take part in its testimony while searching for the lost children—unaccompanied children traveling through the Americas with the hope of settling in the United States—of its title.

W.G. Sebald, The Emigrants (trans. Michael Hulse)

Among all of VHS’s many guides and antecedents, W.G. Sebald’s archival fiction The Emigrants is the one that serves as a lodestar for my novel about transferring stories through different mediums, so diaphanous is Sebald’s mosaic of semi-autobiographical narratives, each chapter devoted to a different person, each of them—Dr. Henry Selvyn, Paul Bereyter, Ambros Adelwarth, and Max Ferber—introducing other persons, with their own stories to tell, each life seeming to be inevitably, intrinsically, implicated by and entangled with any other life in the cadence of time, the passages and intervals of space.

Sebald’s granular narration, and Michael Hulse’s English translation, exploit the looping and layering of storytelling: stories interject, fracture, and overlap; speakers become imbricated until each story—intermittently accompanied, as in other novels by Sebald, by cryptic images—becomes the unnamed narrator’s own story about routes of exile that lead, indeed, everywhere.

______________________________

VHS by Chris Campanioni is available via Clash Books.