When Taylor Swift announced the title of her new album The Tortured Poets Department at the Grammy Awards in February, a question popped into my mind: How can poets and poetry enter into conversation with Swift? As a debut-era Swiftie, I knew that her lyrics contain all of the elements of poetry, and that her songwriting is simply unparalleled and literary.

Article continues after advertisement

As quickly as the question formed in my mind, so did an answer: Ask the best poets writing today to respond with a poem to one specific song of Swift’s without using direct lyrics or titles; then, create a one-of-a-kind ekphrastic poetry anthology which leans into the spirit of Swift’s songwriting, highlighting the way she interacts with her huge fan base whom she has trained to search for “Easter Eggs” in everything from her songwriting to the clothes she wears.

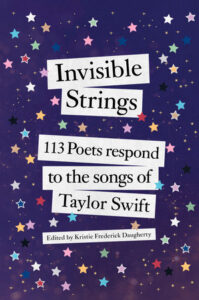

I started with Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Diane Seuss, who not only said yes, but also offered a list of a poets to contact. From that moment the project blossomed into something absolutely beautiful, with 113 poets joyfully agreeing to take part. This is the magic of Taylor Swift: bringing people together through language is what she does best. Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift is designed to bring joy to poetry lovers and Swifties alike with new work from 113 of today’s best poets, including Pulitzer Prize winners, National Book Award winners, New York Times bestsellers, and Instapoets.

–Kristie Frederick Daugherty

*

“Firstborn”

Jeannine Ouellette

Light travels at the speed of light no matter what,

but the rains came hard that summer, the crabapples

dropped early & you were four days late. How happy

I was, just twenty-two & already holding everything

I ever needed. I gave you all I had: my chin, my voice

& my middle name, Marie, which means beloved.

You named me Mama, a far-back ah of saltwater

& round-bellied want whenever I twisted too soon

from your baby sheets. You named the world too—

kitty, book, bye-bye & every other thing, like the arnica

we dabbed on school-day bruises dotting your shins

with little plums & that birthday girl’s crooked meanness,

or mine. Your new selves, too, unfolding, till suddenly

I was just Mom, a short o rusted shut.

Only then did I remember how all of you was always

yours—your chin, your voice & your middle name, Marie,

which also means sea. All seas have two shores, one close,

one far. But aren’t seas also circles? Like the moon?

Look how easily she slips through this familiar darkness

we both hope under & those old stars, too—

thirteen billion years of light, steadfast & ours.

Twinkling Is Just an Effect, from Jeannine Ouellette

We say, this will be over in a heartbeat, but we don’t feel that heartbeat-sized truth until something vanishes, and its absence roots itself into the cavities of our bones, where the marrow makes and remakes our blood. We say, our bones are made of stars, but this is mostly an abstraction until we face our own death, or possibly the death of a true beloved—or, if we are very lucky, the birth of a child. We say things are blinding, but we don’t remember what it means to be blind until we can no longer see whatever blinded us. We say stars twinkle, but they only appear to twinkle in the night sky when viewed from the surface of Earth—twinkling is an effect from the atmosphere. We call our children our children, but Kahlil Gibran warned otherwise more than one hundred years ago in his poem “On Children,” in which he said (in part):

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

We say, life is full of coincidences, but we mean invisible strings. I had never heard my song until Kristie assigned it to me. But the shape of my song was inside me all along, just like the leftover light from my firstborn’s birth. I almost never watch the Grammys, but when Taylor Swift announced her Tortured Poets Department album that night in February, inspiring Kristie to create this anthology, I was watching, too, because my granddaughter and her parents were visiting in the dead center of my eight-week writing retreat on the Gulf of Mexico. Every morning on the Gulf was a spectacle, with the sun rising over St. Vincent Island and pods of dolphins swimming in the shallows outside our window. My part in this daily drama was to read Gibran’s “On Children” aloud to my painter husband, after which he would read Rumi’s “The Guest House” to me. We were working on our bone marrow. Meanwhile, our youngest child was, during this oceanic time, agreeing to adopt the little boy who had come into their life—our lives—through foster care two years earlier. Now this child is officially our grandson, even though our children are not our children, and this being human is a guest house, and things are only ever fleeting and infinite at once.

What strange magic to have Taylor Swift sing such holy truth to me, and to try to sing it back.

*

“The Williams”

Naomi Shihab Nye

In honor of Madison Cloudfeather Nye

Somehow the voices twined around a young mind

encouraging gentle stanzas, open endings,

even in a Texas town where they wanted you

to testify before cashing a check. Heck with that, boys.

I’m heading out in my little gray boots, slim volumes

of poetry in my holster, William of Oregon, William of Maui,

drinking jasmine from an old fence. I’m finding a meadow,

children, dandelion puffs, scraps from a vintage notebook.

The double William of Paterson, New Jersey

helped keep us sane though our teachers

went crazy over that wheelbarrow.

Love it, then move on!

Riding a train north in England to the stoop

of another William’s cottage, sloped roof,

his sister’s purple-scented paper next to his,

high school memory loitering: our teacher

insisting his gloomy poem nearly led

to death. My classmates concurred,

not caring much whether some guy

leapt from a cliff long ago or not,

but I said, He grieves, but he is filled

with joy. In a strange voice

like a ringing bell, immeasurable joy, because

he grieves so much. Because he loves

so deeply all that he is seeing.

They stared at me.

I was never at home in that school.

Our teacher wanted everyone to get

the same thing from a poem.

Later home felt everywhere, radiant waters,

thistles, greenest hilltops dotted with sheep,

masses of tulips and geese, wandering William’s

intricate paths, pausing at every turn,

life stretching ahead, mountains of bliss

and searing sorrow for years to come.

They wrote it, we defended it,

it seemed joyous enough to know one could

love forever, carry on or stop right there,

and the power was yours.

Writing About My Song, from Naomi Shihab Nye

Listening to music is the easiest journey we can take, involving no tickets, the least baggage. I need it when I drive and during Texas summers. I need it when I cook. People ask if I listen to podcasts. No, I listen to music.

Writing in response to Taylor Swift’s song was the most pleasurable trip I’ve had in a while. Her song took me backward and forward, linking a few elements I might never have connected—a teen memory (high school English class) and my current grief (too many deaths of loved ones in quick succession). This stun-gun era has been overlaid by the genocide of innocent people I also think of as my own—Gazans, and Israelis, too. Innocent people, children. They’re all mine, all ours. It’s as if the better instincts of human beings have been betrayed. Every religion, every moral or ethical code, every good intention/fizz.

How do we put anything together? Is it possible to renovate our personal sense of wreckage to be any person we ever tried to be? Taylor helps me do that. She often does. This past sad Christmas, all I wanted to do was watch her Eras tour for three hours and travel out of my body. My assigned song in this project gave me a gift of our son I hadn’t anticipated. He often listened to the same song on repeat for days. Ritual helps us survive.

*

“The Long Marriage”

Victoria Redel

Sometimes when we’re at the table

with others, I can’t concentrate

remembering the way your foot fit

down through your jeans, & poked

out tendoned and arched before

standing on the wood floor. Someone

is saying something about the siege

of our ragged world, the bully

on the playground, the correct

fruit to eat, but I’m too distracted

recalling your muscled arm reaching

through the t-shirt you wear like silk.

Our best friends are quick

to claim justice but who’s to say

it happened just that way;

I only know I’ve been wrong

more days than right.

Let them keep insisting

they invented taboo,

but if the talk ever twists

to a pleasure investigation,

I won’t tell who spilled the wine

whose lilac heels were in whose hands?

Behind closed doors

everything’s invention, ours

to carve on walls.

We both know the best place

for that gold dress

was floating to the ground.

It’s practically an insurrection

each time jeans slide off

your hips, but who’d believe

the two of us are still up

for this much disruption.

I’ve been patient long enough,

it’s past this old girl’s hour,

let me take you out

into the undressed night,

let’s shiver, let’s shake.

I’ll swipe my lips red,

& drag you off to bed.

The Gift, from Victoria Redel

When I was a kid, I loved to play the same song over and over and over, lifting the record player’s arm to settle it down on the vinyl’s first beats or strums of whatever was my new favorite song that week or month. The endless repetition drove my family crazy. This invitation to write in response to an assigned Taylor Swift song brought me back to that pleasure as I turned up the volume and listened to the song again and again. Oh, to lose oneself to something larger and in that abandonment to find oneself in a deeper and truer place! Isn’t that the great mystery and delight in poetry and music, in dance and painting? But in the days before I wrote my poem, it had been impossible to lose myself—the attentions of the world so insistent and grave. Taylor Swift’s song was a gift I needed.

From the very first time I blasted Taylor singing this song, I knew I wanted to celebrate the life force, the wild erotic that endures. If Taylor’s song was a present for me, I wanted to make her a gift—a promise that passionate intensity needn’t burn out with age. It’s there for the claiming. That touch continues to blaze and heal. With each draft of the poem, I pushed myself to go further, playing with Swift’s imagery and rhythms, to revel in ecstatic intimacy, in the enduring beautiful private that can occur between people.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift by Kristie Frederick Daugherty. “Firstborn” by Jeannine Ouellette, copyright © 2024 by Jeannine Ouellette. “The Williams” by Naomi Shihab Nye, copyright © 2024 by Naomi Shihab Nye. “The Long Marriage” by Victoria Redel. Copyright © 2024 by Victoria Redel. Used by permission of Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.